It’s Time to Sync Up: The Reason WWVB Exists

WWVB started not as a radio station, but as a measurement problem in need of a reliable solution. By the middle of the 20th century, the United States had reached a quiet inflection point. Electrical, telecom, and broadcast providers; transportation and government services; even everyday consumers were becoming ever more dependent on synchronized timekeeping—and the precision required was also on the rise.

The country needed a single, stable, and accurate reference clock that could be delivered by radio signal and utilized directly by equipment of the day.

At the time, the charter of the National Bureau of Standards was to ensure that measurements meant the same thing everywhere in the United States—not just in laboratories, but in real operational systems.

- Isolated rural electric power grids were expanding and interconnecting and had to deliver AC power at precisely 60Hz without compromise.

- Long-distance telephone networks were time-slicing multiple phone calls onto interleaved trunks that required precise timing to encode and decode.

- TV and radio broadcasters needed precise timing not only to keep programming on schedule but to ensure their transmitters were calibrated to a known reference frequency.

- Prior to GPS, radio-navigation beacons required a closely synchronized timing.

It was clear that commercial, scientific, and industrial users required an authoritative reference they could trust without maintaining their own standards and WWVB was built specifically to satisfy that need.

The Nation Needed a Consistent Source of Timing

At the time of its commissioning, WWVB’s primary design goal was to extend the National Bureau of Standards’ laboratory time and frequency precision across the continent in the form of a continuous radio transmission. Its role was to provide a common and continuous heartbeat that disparate systems across the country could all align with—something no other technology of the era could do as reliably or as broadly.

Inside the laboratories of the National Bureau of Standards, engineers and physicists could already generate exquisitely stable frequency and time references. That part of the problem had been solved. What was not solvable—at least not yet—was how to distribute that reference reliably to the rest of the country.

The requirement was deceptively simple and sounded almost impossible: Make the nation’s definition of time and frequency accessible everywhere, continuously, and without sophisticated receivers or large antennas. The signal had to be consistently accurate, reliable, and easy to receive. It had to work in remote areas and in electrically noisy cities; in factories and in laboratories; both indoors and out. And once built, it had to run for decades with minimal intervention or maintenance. These requirements immediately ruled out elegant solutions; this was going to get ugly. This was a serious engineering challenge that would take years to complete.

Using Radio to Deliver a Precise Timing Signal

A powerful HF station could cover the long distances, but HF is too flaky and erratic. HF relies on ionospheric propagation that changes with time of day, season, and solar cycle. Frequency stability on HF is affected by fading and multipath. For a service meant to define the standard of time, propagation-induced frequency drift was completely unacceptable. Delivery over higher frequencies was ruled out because that would require repeaters and other infrastructure that would introduce even more unpredictable latency.

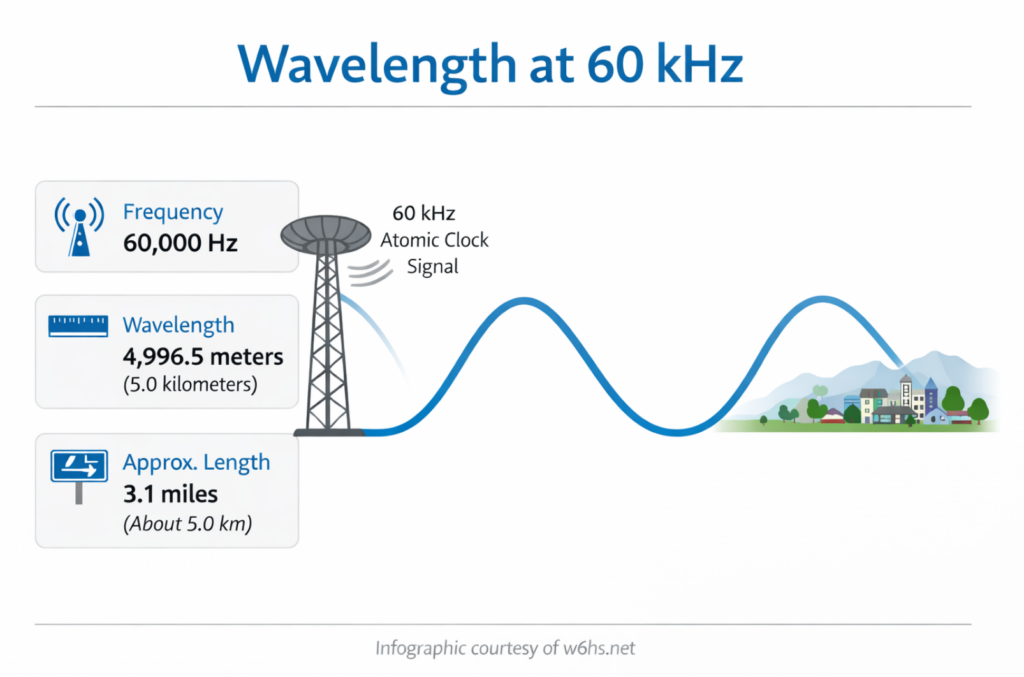

Instead, Bureau engineers went down in frequency. Like way down. Down to just 60 kilohertz.

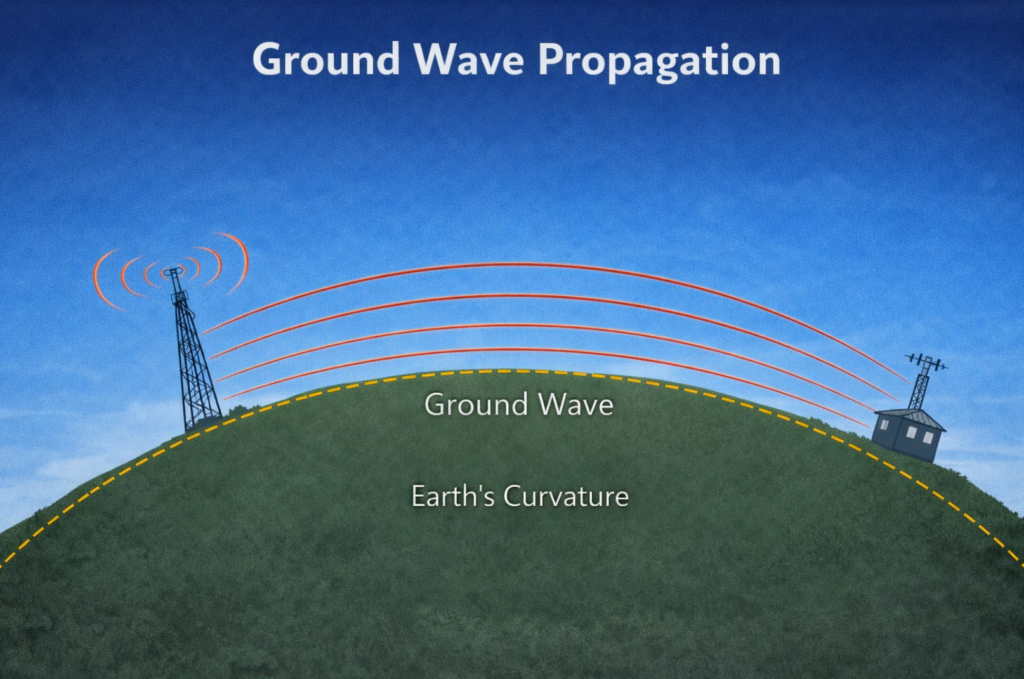

Very low frequency offers predictable behavior that can be trusted. Ground-wave propagation was well understood at the time and is remarkably stable. Signals follow the Earth instead of bouncing around unpredictably in the atmosphere. Phase and amplitude change gradually and predictably. Noise is higher—but it is also statistically consistent—something engineers could design around.

Choosing VLF solved the propagation problem but immediately created an antenna problem of staggering proportions. At 60 kHz, the wavelength for this new radio service would be nearly five kilometers long and to get it a quarter-wave off the ground would put it a mile or so in the sky.

No practical antenna could ever reach a meaningful fraction of this 5km wavelength. Radiation resistance would be vanishingly small; losses would be through the roof; and efficiency, in the conventional sense, would be pretty terrible as well.

Bureau engineers knew this before a single tower was ever planted in the ground. Historical records and early technical reports make it clear that antenna efficiency was not the primary goal. Antenna design was almost an afterthought. No, this thing was being built for reliability and accuracy. The station had to run continuously and with very little maintenance for decades.

When Antennas Principles Stop Making Sense

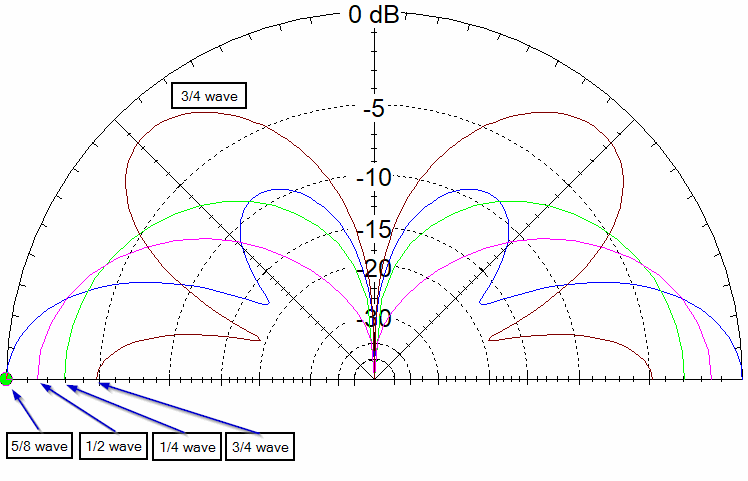

Every radio amateur carries around a set of antenna instincts. We learn these instincts early on and we trust them deeply because we have experience with them and we know them to be true.

- Make the antenna a useful fraction of a wavelength.

- Control current distribution.

- Reduce losses.

- Get energy to detach cleanly from the structure and become a traveling wave.

If you do those things, radiation happens. That’s the magic of radio in action. Those instincts are driven by laws of physics and they’re inherently predictable—until you wander into VLF territory.

At 60 kHz, the wavelength is so large that the antenna problem stops looking like a simple geometry problem and starts looking more like a field management problem. This is where the designers of WWVB had to make a mental shift.

The first realization was blunt and unavoidable: They would never achieve an efficient resonant radiator in the conventional sense. The radiation resistance of a short vertical at VLF would be measured in milliohms or less. Meanwhile, ground resistance and conductor losses would remain orders of magnitude higher. By the math alone, efficiency is doomed.

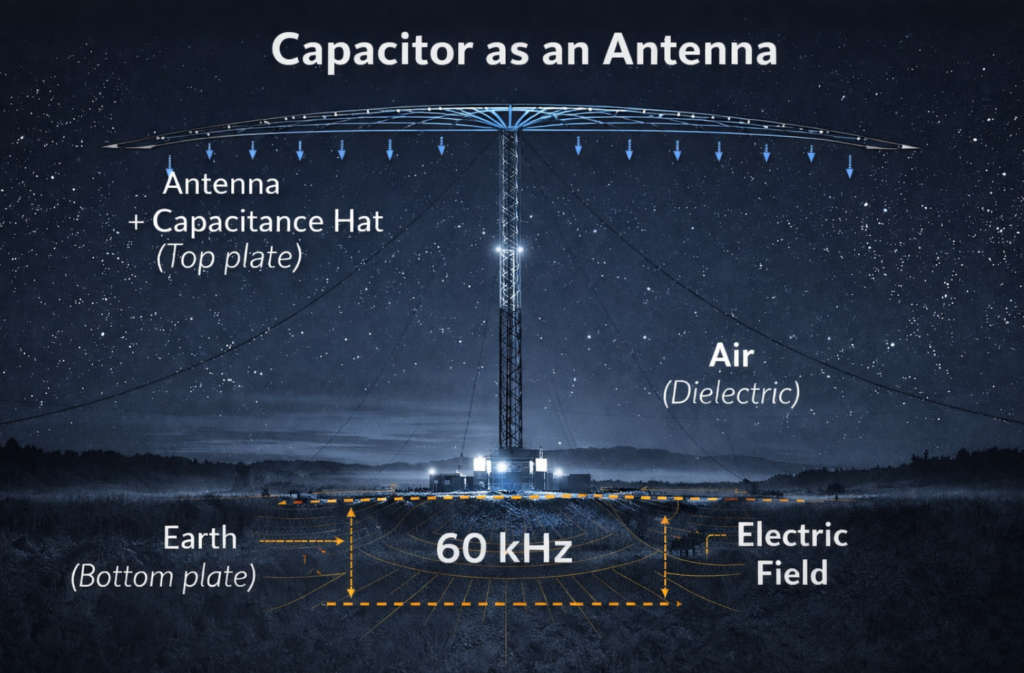

So, instead of asking “how do we radiate more power?” hey asked “what does the transmitter actually do to the earth’s electromagnetic field at this scale?” To answer that, it helps to temporarily forget antennas and think about capacitors.

A capacitor is one of the simplest components in electronics. Two conductive surfaces separated by an insulator. Apply a voltage, and charge accumulates. An electric field forms in the space between them. Reverse the voltage, and the field reverses. No electrons cross the gap, yet energy clearly moves.

A Capacitor as an Antenna?

At VLF, the WWVB antenna system behaves like one plate of a capacitor, with the Earth itself acting as the other plate and the atmosphere in between as the dielectric. The enormous top-loading structures—the famous “capacitance hats” as they’re called—exist not to shape a radiation pattern, but to increase the effective surface area of the upper plate. More surface area means more capacitance. More capacitance means more stored electric field for a given voltage swing.

Imagine a tall conductive hammock-like structure rising above the ground. Beneath it, an extensive network of buried radials bonded deep into the Earth. Between them: Nothing but air. The moment you drive voltage onto the structure, an electric field forms between the metal hat and the soil. When the voltage changes, the field changes. When the polarity reverses, the field reverses.

This is the first conceptual hurdle for many hams, because we’re trained to think of stored energy as the enemy. Reactance is something we neutralize, tune out, or minimize. At HF, excessive stored energy usually means poor radiation efficiency and a notable standing wave. At VLF, that stored energy sloshing back and forth is the name of the game.

Oscillation in the field produces what Maxwell called displacement current, a current that exists not because charges are flowing through a conductor, but because the electric field itself is changing. Nothing about this process requires efficient radiation. In fact, radiation is incidental. For now, we’re just building a stable electrical field between the two enormous plates of our capacitor.

When WWVB’s transmitter drives the antenna, most of the power does not leave as radiation. Instead, it goes into building and maintaining the massive electrical field between the antenna and the Earth. That field expands outward, filling space, then collapses as the polarity reverses. This happens sixty thousand times per second, relentlessly, and with exquisite precision.

How Does WWVB’s VLF Signal Propagate?

The answer lies at the boundary of our planet and its atmosphere. The Earth is not a perfect conductor, and the air above it is not a perfect insulator. The interface between the two is a lossy, imperfect medium that responds to changing electric fields. When WWVB’s antenna’s field oscillates, it does not remain perfectly confined. A small fraction of the energy couples into the surface of the Earth and propagates outward as a ground wave.

This is why the radial network and grounding system is fundamental to the station’s efficiency. The radials buried beneath WWVB are not there just to reduce loss resistance in the usual sense. They define the electrical relationship between the antenna and the Earth. Soil conductivity, moisture content, bonding integrity—all of it affects how efficiently the oscillating field couples into a usable propagating wave.

We’re used to designing antennas that radiate first and store energy reluctantly. WWVB stores energy eagerly in its electric field and radiates reluctantly as a form of loss. But because it does so continuously, the radiated component—however small at any instant—adds up to a usable, stable signal when accumulated over time.

Slow on Purpose: One Bit Per Second

Once you accept that WWVB’s antenna is really a gigantic field-coupling device—charging and discharging the Earth itself—the next design choice makes sense: The data rate is glacially slow at just one bit per second. It takes a full minute to move a complete frame of data.

Simple Elegance is Design’s Best Friend

The core of the WWVB time code is deceptively simple. The carrier at 60 kHz never stops. Instead of turning the signal on and off to encode data, amplitude is gently shifted up and down for brief periods of time. It’s this amplitude-shift keying that allows for transfer of binary data.

The choice to use subtle variations in amplitude reflects Bureau engineers’ deep understanding of the environment that WWVB would be operating in. At VLF, atmospheric noise is a huge problem, especially from thunderstorms. Global lightning activity, other natural electrical phenomena, and man-made devices raise the noise floor dramatically compared to HF or VHF. Trying to outrun the noise with fancy protocols would be futile. Instead, the designers chose a slow and steady approach: Let the signal accumulate.

One bit per second allows receivers to integrate energy over long periods of time. A radio-controlled clock doesn’t need to decide instantly whether it heard a one or a zero. It can average, compare, and slowly build confidence. Noise spikes come and go but the signal remains and eventually will be heard.

How Does Integration Work?

In a typical WWVB consumer receiver, integration happens on two overlapping time scales.

At the bit level, the receiver integrates over a few hundred milliseconds per second, usually on the order of 100–800 ms. This is long enough to smooth out noise and clearly detect whether the carrier’s amplitude was reduced for 200, 500, or 800 milliseconds, which is how individual zeroes, ones, and markers are encoded.

At the frame level, the receiver integrates much longer—sometimes several minutes or hours. A complete WWVB time frame takes one minute to transfer, but most clocks will require multiple clean data frames before they’re trusted. Indoors or in noisy environments, many consumer clocks will integrate over several hours or days, averaging repeated frames until the decoded time is stable and error-free.

So while the signal processing integration happens in fractions of a second, the time-setting confidence integration happens over much longer periods, which is why WWVB clocks are slow to synchronize but incredibly stable and reliable once they do.

Atomic Precision Delivered Continuously

WWVB’s greatest trick is not that it broadcasts time. It’s that it hides the complexity of atomic timekeeping behind an intentionally simple radio signal, making these incredibly precise measurements available to everyone.

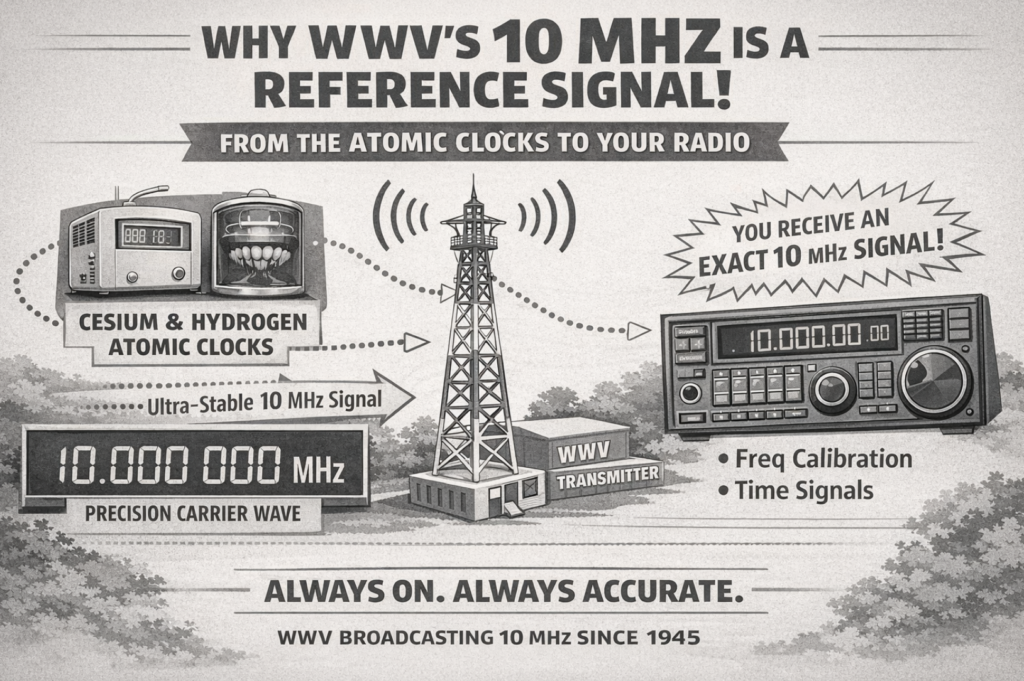

Nowadays, a modernized WWVB is operated by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, successor to the National Bureau of Standards. NIST does not rely on a single atomic clock, nor even a single type of atomic clock. Instead, NIST maintains an ensemble of frequency standards, including cesium fountain clocks and hydrogen masers, each with different strengths.

Cesium fountains provide unmatched long-term accuracy. Hydrogen masers excel at short-term stability. By comparing and combining them, NIST creates a time scale that is both extraordinarily stable and traceable to the definition of the second itself. This ensemble approach matters, because no physical clock—no matter how advanced—is perfect in isolation. Precision emerges from comparison.

The cesium clocks produce an extremely stable 10MHz reference signal. This signal provides perfect discipline for WWV’s HF oscillator and gets synthesized down to a 60kHz phased-locked signal that feeds the exciter driving WWVB.

The signal broadcast from Fort Collins is not a raw feed of atomic seconds ticking by. It is a carefully managed representation of time that prioritizes continuity and predictability over immediacy. The transmitted time is intentionally offset, allowing adjustments to be made smoothly, with leap seconds announced far in advance.

From an engineering standpoint, this is an elegant compromise. Atomic clocks are capable of astonishing precision, but that precision is useless if it can’t be utilized. WWVB acts as a buffer between the uncompromising world of atomic physics and the mountain of cheap radio receivers scattered across the continent by speaking both languages. Not surprisingly, WWVB is still relevant, important, and utilized.